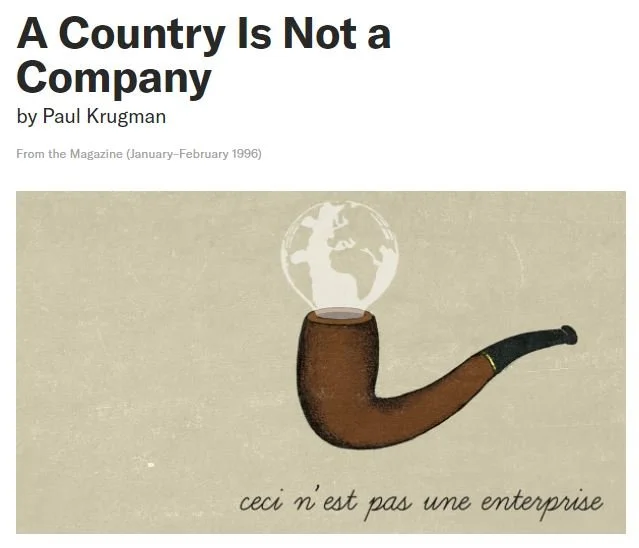

You can't run a country like a company

The HBR wisdom comes from 1996 and made sense then, before and now. It is generally a mistake choosing business people to run countries. The bigger, huge, mistake is that the individuals themselves are unaware of their limitations . . .

The idea that a country should be run like a business is a familiar refrain in conservative politics. It sounds efficient, even responsible: cut waste, balance the books, get results. But in practice, applying corporate logic to public governance has repeatedly failed to deliver for ordinary people. This ideology (yes, it’s an ideology!) has been sold to New Zealanders as common sense - it is far from that.

The Flawed Business Analogy

At the core of the conservative model is the belief that government should act like a CEO: trim costs, reward performance, and avoid “interference” in the market. But this model ignores the basic truth that countries are not companies. A government’s job is not to generate a surplus but to serve the public good—an aim that often requires investment in areas that don’t produce a financial return, like public health, education, or cultural preservation.

New Zealand’s embrace of neoliberalism in the 1980s and 1990s—led by both Labour and National governments—was a textbook case of conservative, market-driven reform. State assets were sold, welfare was slashed, and public services were cut back in the name of “efficiency.” While these policies improved some macroeconomic indicators, they also entrenched inequality, hollowed out local communities, and left vital infrastructure underfunded.

Conservative economic policies often promote austerity as a virtue. But what they label as “fiscal responsibility” often translates into real hardship for real people. In New Zealand, this approach has disproportionately hurt Māori, Pasifika, and low-income families. Cuts to social welfare, user-pays models in education and healthcare, and underinvestment in public housing haven’t just left gaps—they’ve deepened divides.

Meanwhile, the market was expected to solve societies problems. The result? A housing crisis, persistent child poverty, and a healthcare system stretched to its limits. None of these are market failures—they are policy choices.

One of the most insidious effects of running a country like a business is the obsession with short-term metrics. Conservative governments often tout surpluses and credit ratings while neglecting long-term investments in climate resilience, education reform, and social cohesion. The National Party’s past resistance to strong climate action is a telling example: prioritising economic “competitiveness” over environmental responsibility may look good on a balance sheet, but it undermines the country’s future.

New Zealand’s Zero Carbon Act and investments in renewable energy were pushed forward not by conservative governments but in spite of them—driven by public demand and progressive pressure. Left to market logic, these initiatives would still be languishing.

Conservative policy tends to frame citizens as consumers: passive recipients of services, responsible for their own outcomes. But real democracy demands more. It requires that people are treated not as economic units, but as members of a shared society—with rights, needs, and responsibilities that cannot be outsourced or priced.

Public services aren’t failing because they’re run by government departments—they’re failing because they’re being run like businesses, with KPIs instead of care. Schools, hospitals, and social agencies aren’t meant to turn profits; they’re meant to build human potential. That’s the work of government—not management.

New Zealand’s recent history shows that running a country like a company is not just misguided—it’s harmful. Conservative policies that idolise the market and shrink the state might appeal to spreadsheets and slogans, but they fail to meet the real needs of a complex, diverse, and interdependent society. A nation is not a balance sheet. It’s a community—and it deserves real leadership, not management.